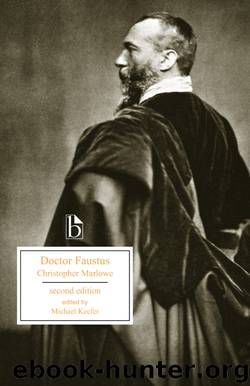

Doctor Faustus, second edition by Christopher Marlowe

Author:Christopher Marlowe [Marlowe, Christopher]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: EPUB9781460400869-8890

Publisher: Broadview Press

Published: 2007-03-14T16:00:00+00:00

3. me thinkes] Modernized spelling would upset the rhythm of this line.

11. determined with] settled among.

17. for that] because.

22. Sir Paris] Ward identifies “Sir” as “the chivalrous prefix of mediaeval romance,” and notes for comparison Pistol’s “Sir Pandarus of Troy” and “Sir Actaeon” in The Merry Wives of Windsor I. iii. 65 and II. i. 105.

23. spoils] booty, including Helen, taken from Menelaus, king of Sparta.

Dardania] Troy, referred to here by the name of the founder of the Trojan dynasty, Dardanus. Compare Shakespeare, Troilus and Cressida, Prologue, line 13: “On Dardan plains”.

27. pursu’d] sought to punish or avenge (OED, v. I. i.b).

28. rape] abduction.

29.] This line echoes Spenser, Faerie Queene III. i. 26: “Whose sovereign beauty hath no living peer” (see Cheney 1997: 196).

35-46.] This speech, which modulates after line 40 into a harsh denunciation of Faustus’s sinfulness as so disgusting and corrupting that only Christ’s mercy and the blood of his redemptive sacrifice can possibly save him, is replaced in B1 by a longer speech of a wholly different theological orientation. The Old Man’s words in A1 are Calvinist in their implication that the consequence of sin is “loathsome filthiness,” i.e., that sinful humanity is radically unloveable, and that salvation can come only as a wholly unmerited consequence of an act of divine mercy. Stachniewski cites many instances from the period of Calvinist domination of Anglican orthodoxy (from the 1560s to the mid-seventeenth century) in which Calvinist theology and preaching produced reactions like that of Faustus in line 48 (see Stachniewski 17-54). He notes that “Many actual suicides resulted from religious despair. Cambridge was notorious for them in the 1580s and 1590s, the period of its greatest domination by puritan preaching” (49). In B1, in contrast, the Old Man tells Faustus, in Augustinian terms, that his soul remains loveable unless perverted by the habit or custom of sinfulness, and he speaks in tones not of “wrath” but of “tender love.”

36. the way of life] The Old Man’s speech, as Ormerod and Wortham note, is laden with biblical echoes and cadences; these words, for example, resonate with Psalm 16: 11, Proverbs 10: 17, John 14: 6, and Acts 2: 28.

43. flagitious] extremely wicked, infamous.

45-46.] Compare Revelation 1: 5: “Jesus Christ … loved us, and washed us from our sins in his blood.” The Prayer-Book of Queen Elizabeth (1559) specifies that if a person in “extremity of sickness … do truly repent him of his sins, and steadfastly believe that Jesus Christ … shed his blood for his redemption” (135), this is the equivalent of taking communion. Faustus is unable so to believe; one interpretation of the blood-pact which he made in II. i (and renews in this scene) is that it amounts to a self-exclusion, through the shedding of his own blood, from the number of those for whom Christ’s redeeming blood was shed. (See the note to II. i. 58.)

47. Where art thou, Faustus?] Bevington and Rasmussen (188) suggest a comparison with Genesis 3: 9: “the Lord God called to the man, and said unto him, Where art thou?”

48.

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

Still Me by Jojo Moyes(11239)

On the Yard (New York Review Books Classics) by Braly Malcolm(5519)

A Year in the Merde by Stephen Clarke(5396)

Eleanor Oliphant Is Completely Fine by Gail Honeyman(5252)

The Bookshop by Penelope Fitzgerald(3827)

How Music Works by David Byrne(3245)

Surprise Me by Kinsella Sophie(3103)

Pharaoh by Wilbur Smith(2984)

Why I Write by George Orwell(2933)

A Column of Fire by Ken Follett(2595)

Churchill by Paul Johnson(2564)

The Beach by Alex Garland(2549)

The Songlines by Bruce Chatwin(2538)

Aubrey–Maturin 02 - [1803-04] - Post Captain by Patrick O'Brian(2296)

Heartless by Mary Balogh(2248)

Elizabeth by Philippa Jones(2189)

Hitler by Ian Kershaw(2183)

Life of Elizabeth I by Alison Weir(2067)

Harry Potter and the Cursed Child by J. K. Rowling & John Tiffany & Jack Thorne(2052)